What Happens When a VC Firm Goes Public?

Lessons from Molten Ventures, SoftBank, and Allied Minds on the risks and rewards of IPO'ing a venture fund.

Hiya, it's been a while since you heard from me!

After a long day working with founders, I found myself thinking about something unconventional:

What if a venture firm raised capital like a startup — and even went public?

It’s rare, but not unheard of. And when it happens, it flips the traditional VC model on its head.

Most venture firms operate on a tried-and-true model: raise capital from limited partners (LPs), invest in startups, return capital after 10 years, rinse and repeat. But what if instead of LPs, a VC firm raised equity as a corporation and then listed on a stock exchange? Let’s explore why this model is so unusual, how a few firms have tried it, and what their stories tell us about the future of VC at scale.

Why do VCs Rarely IPO?

Traditional venture capital is built around the limited partnership model:

General Partners (GPs) manage the fund.

Limited Partners (LPs) commit capital for a fixed period (usually 10 years).

Returns are shared through management fees and carried interest.

Liquidity only comes when investments exit.

This model works well for long-term investing, but it’s not built for public markets.

Why?

Venture returns are lumpy and illiquid

Valuations are often opaque

Public markets expect quarterly updates, not decade-long holds

What If You Raised Equity Instead of LP Funds?

A few bold firms have flipped the model. Instead of raising LP capital, they raise equity, either privately or through an IPO, and use it to invest in startups. This creates a permanent capital vehicle with public liquidity. In this model:

Capital is raised via equity (private or public), not LP commitments.

The VC firm becomes a listed investment company

Public shareholders own equity in the VC firm itself

The firm invests in startups off its own balance sheet

The upside?

- Access to permanent capital

- More flexibility

- Public exposure to private startupsThe downside?

- Short-term shareholder pressure

- Valuation transparency issues

- Risk of misalignment between public investors and long-term startup bets

Who tried it?

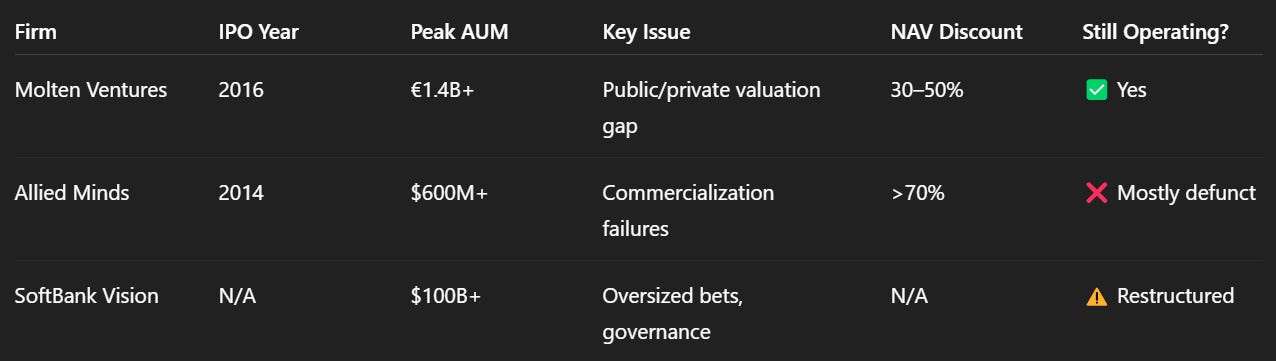

I did some digging. Turns out a few firms have experimented with this model — with mixed results. Here are the three most notable:

1. Molten Ventures (formerly Draper Esprit) – UK

IPO Year: 2016

Listed On: London Stock Exchange

AUM: €1.4B+

Key Investments: UiPath, Revolut, Graphcore

2. Allied Minds – US/UK

IPO Year: 2014

Listed On: London Stock Exchange

Model: Spun-out IP from U.S. federal labs and universities

3. SoftBank Vision Fund – Japan

Launched: 2017

AUM: $100B+

Structure: Corporate fund, not traditional LP-GP

Backers: SoftBank equity, Saudi PIF, Mubadala, debt financing

What does the data say? Here’s how these three firms compare:

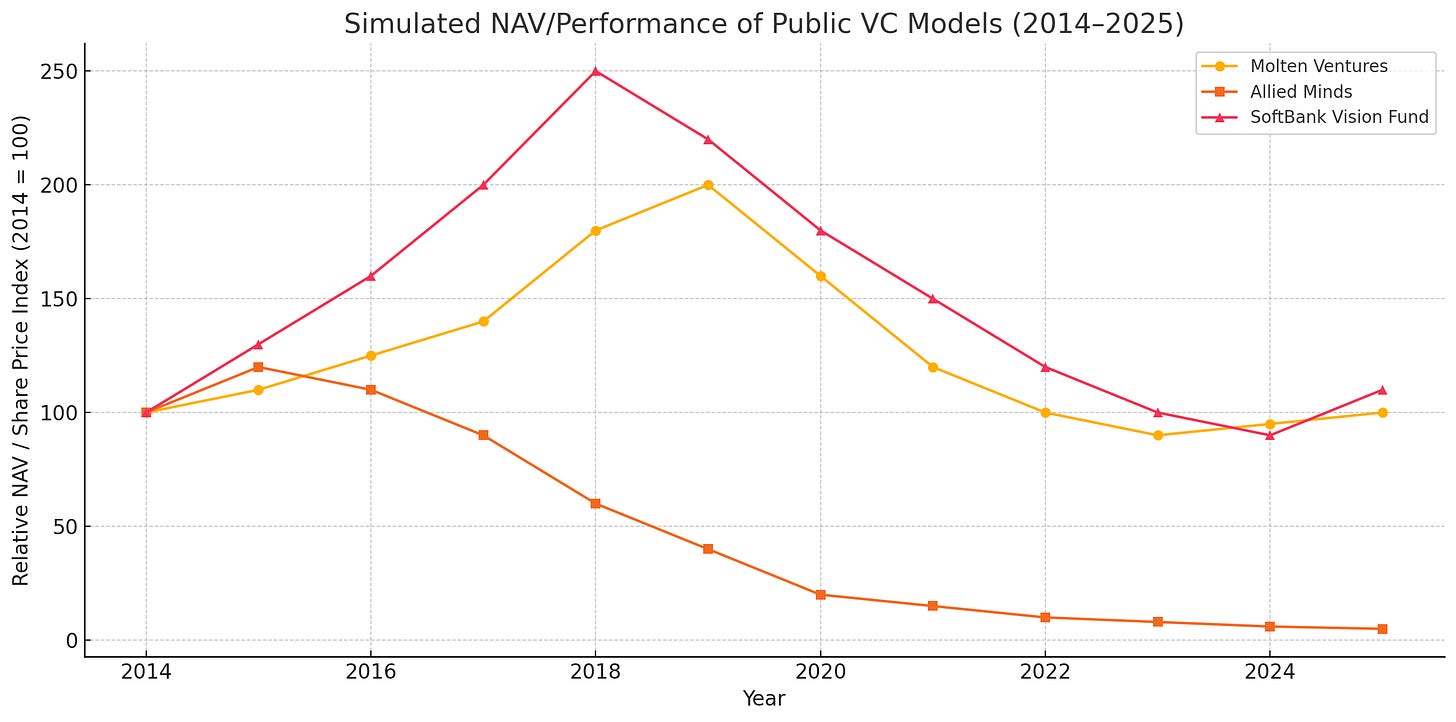

Here is the simulated performance chart of the three venture investment models from 2014 to 2025:

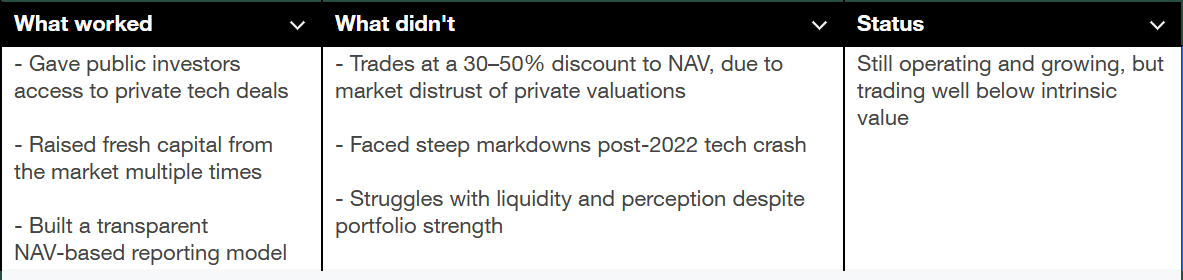

Molten Ventures: Peaked around 2020–2021, dipped post-tech crash, and is gradually recovering.

Allied Minds: Rapid decline after 2015 due to commercial failures—essentially a collapse story.

SoftBank Vision Fund: Soared during the tech boom but faced steep losses during the downturn before a modest rebound.

So, is it scalable?

Yes, but with a lot of caveats. It’s only scalable if you have strong internal governance, portfolio performance is transparent and measurable, and most importantly, your investor base understands long-term, illiquid bets and you align incentives like performance-based equity and not short-term compensation. Yes, you guessed right — the last two are not characteristic of public investors.

It’s not scalable if you try to “blitzscale” like a tech startup, or chase momentum without deep diligence, or rely on quarterly stock performance to fund long-term bets.

Verdict?

The idea of IPO’ing a VC firm may sound wild, but it offers a path to permanent capital and long-term scale. If anything, it’s a glimpse of a future where:

Retail and institutional investors can access private markets

Venture capital evolves into a more liquid, transparent asset class

Think of it like the REIT model for startups: steady, visible, and long-term — if you build it right.

Public venture capital might not replace the traditional LP-GP structure, but it could become a viable alternative, especially in markets hungry for exposure to high-growth private companies.

Think of it as the REIT model for startups: transparent, liquid, and long-term, but only if you build it right.

Want more deep dives like this? Subscribe to the newsletter for weekly takes on venture innovation, capital markets, and the future of investing.